One of the great current exhibitions in the city is of the city. It is taking place at the Museum of the City of New York on Fifth Avenue at 103rd Street. The museum has become a vital place to experience exciting exhibits on relevant themes connected to our urban history.

One of the most outstanding, “The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011,” explores the impacts of the 1811 Commissioners’ Plan, whose bicentennial is being celebrated in this exhibit, on the people and natural terrain of New York.

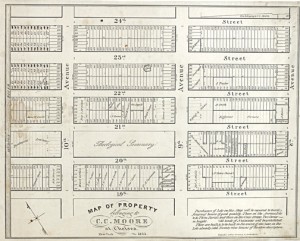

This plan was the beginning of the great wipeout of almost all of the new city’s rural character and history north of First Street on the East Side and Eighth Street on the West Side all the way up to 155th Street. This was not the first grid. Even New Amsterdam was laid out in a modified grid in the 17th century. All of present day Lower Manhattan was laid out in a series of arbitrarily canted grids. This was, however, the first grid laid out for the balance of Manhattan and for the bank balances of its property owners, including Astor, Bleecker, Moore, Stuyvesant, and other major landowners. The grid allowed for auctions of scattered properties on mapped streets without any geographic priorities. Few parks or other public facilities were provided. No allowances were made for terrain, shoreline, streams, wetlands, rock outcrops, woodlands, fields or other natural features. It was a street system drawn by a computer running a program in sleep mode.

The Commissioners’ Plan was laid out in the field by civil engineer, John Randel, Jr., who wrote in his report to the Commissioners, “From the crossing place I followed a well-beaten path leading from the city to the then Village of Greenwich, passing over open and partly fenced lots and fields….” The commissioners, including Simeon De Witt, Gouverneur Morris and John Rutherford, were enamored of the rational clarity of the grid, with its enormous development potential of more than 150,000 building lots if the irregular terrain was filled, cut and smoothed out. This is the same clarity that was admired by the French planner and architect, Le Corbusier, discussed in “Walking in Paris: Streets that Work” (November WestView). A copy of Le Corbusier’s “Quand Les Cathedrales Etaient Blanches: Voyages Au Pays Du Timides” (“When the Cathedrals Were White: Voyage to the Land of the Timid”), published in 1937, is on display in the exhibit, along with a 1935 copy of American Architect in which he is quoted in an article entitled “La Ville Radieuse” as complaining that American skyscrapers were too small. “Height is a thing beautiful in itself,” he exulted, proposing that blocks be aggregated into larger units with lower buildings cleared at the bases of skyscrapers. Coincidentally, Florent Morellet complained at his show, “Come Hell or High Water,” at the Christopher Henry Gallery (December WestView), that Paris was passing into obscurity because of its failure to build tall buildings.

The high point of The Greatest Grid show is the display of John Randel’s original drawings: water color and ink depictions of then still existing farm lanes, fences, walls, ponds, streams, wetlands, hills and buildings that bring to mind the exquisitely painted murals in the Egyptian Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photographs show the depredations visited on farmers whose homes were left isolated on inaccessible steep hills by the deep excavations for the street grid. Livelihoods and history were destroyed by an action so extreme as to make the Lower Manhattan Expressway once proposed by Robert Moses a comparatively inconspicuous change to the urban fabric.

The plan was criticized by such luminaries as Edgar Allen Poe who complained that “these magnificent places are doomed. The spirit of improvement has withered them with its acrid breath.” Frederick Law Olmsted, who, with Calvert Vaux, designed Central and Prospect Parks, which respected land forms, as antidotes to the grid, reacted similarly, saying that the grid had all the creativity of “the chance occurrence of a mason’s sieve near the map of the ground to be laid out.” Jane Jacobs, whose name exhibition curator Hilary Ballon invokes as a supporter of the grid, in fact was also critical, writing in “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” that she understood why European visitors often remark that “the ugliness of our cities is owing to our gridiron street systems.” She added that “if such a street goes on and on into the distance . . . dribbling into endless amorphous repetitions of itself and finally petering into the utter anonymity of distances, we are also getting a visual announcement that clearly says endlessness.”

What could have been the alternative? Certainly not the axial stars of Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s Washington, D.C., as other critics proposed. A thoughtful plan would have required real vision and hard work and would have looked at the varied and prominent physical features shaping the island: its hills, valleys, water courses and, most especially, its shoreline. City planners could have incorporated these features into the city’s streets and park system, which they in fact did in the building of such parks as Riverside, Central, Morningside, St. Nicholas, Colonial, Mount Morris, Highbridge, Inwood Hill, Fort Washington and Fort Tryon Parks. However, these were largely steep hillside remnants, unsuitable for buildings and equally unsuitable for recreation. We have to look to other cities for creative, beautiful alternatives to the mindless grid. London has Admiralty Arch and the magnificent Regent and Portland Streets, created by John Nash, with their edges defined by the facades and roof lines of his architecture: Pall Mall; Marble Arch; Trafalgar Square. There is Bath, with its Royal Crescent and many small squares; Edinburgh, with its bi-level West Bow and New Town; Barcelona, Spain, and Savannah, Georgia, with their extraordinary squares; the Piazza del Campo in Siena; the Piazza Navona in Rome; and, most rewarding of all, the center of Paris, built on the fabric of a medieval city (November WestView), where narrow streets curve and bend, providing mystery, welcome surprises and new experiences along the way. Our own Greenwich Village, fortunately spared by the Commissioners in 1811, contains these qualities. Broadway, the longest street in Manhattan, slices through the grid at an angle to the north and south, providing a series of triangular parks, called “squares” strung out like beads on a necklace, following a former Indian trail and the historic Bloomingdale Road.

The tail end of The Greatest Grid exhibition provides a large number of alternative visions of what Manhattan might have become. One in particular responded to the basic terrain of the island. This was Barton Robb’s “Apple Hamlet.” There is much to see in this and other shows at the Museum of the City of New York, requiring repeat visits. The Greatest Grid will run through April 15.

By Barry Benepe

“The Greatest Grid”

Museum of the City of New York

1220 Fifth Avenue at 103rd Street

Through April 15

212-534-1672/ mcny.org

Yes! Finally someone writes about surf fishing gear bags.